-

Categories

-

Pharmaceutical Intermediates

-

Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients

-

Food Additives

- Industrial Coatings

- Agrochemicals

- Dyes and Pigments

- Surfactant

- Flavors and Fragrances

- Chemical Reagents

- Catalyst and Auxiliary

- Natural Products

- Inorganic Chemistry

-

Organic Chemistry

-

Biochemical Engineering

- Analytical Chemistry

-

Cosmetic Ingredient

- Water Treatment Chemical

-

Pharmaceutical Intermediates

Promotion

ECHEMI Mall

Wholesale

Weekly Price

Exhibition

News

-

Trade Service

One bacterium sticks out its fimbriae, connecting to another (Credit: UCR) The microbes in our gut regularly 'sex', which is, in a way, a good thing for both the bacteria and us

.

Written by | Reviewed by 27 | Chestnuts As you probably know, there are a lot of bacteria living in our intestines

.

And what you might not know is that in order to survive better, these bacteria "have sex" on a regular basis

.

Wait, bacteria don't seem to have strictly genitals, and they don't have gender divisions, so can they have sex? In our impression, bacteria reproduce by division, without the "worldly troubles" of mating

.

But under the biological definition, the essence of sex is the exchange of genetic material

.

A recent study published in Cell Reports shows that bacteria in our gut can stick out a tube called a pilus to "inject" their DNA into another bacterium, helping others Bacteria have the ability to obtain vitamin B12

.

For these seemingly simple life forms, although not related to the reproductive process, this is their "sex life"

.

The "sex life" of bacteria In fact, bacteria also have "sex life", which scientists have discovered a long time ago

.

In 1946, Edward Tatum and Joshua Lederberg first discovered that there is also the exchange of genes between bacteria

.

Tatum and Lederberg obtained two mutants of the Escherichia coli K12 strain by chemical induction

.

Both mutants were unable to synthesize certain essential nutrients, so they could not survive in the natural environment, and could only grow in a laboratory environment where the corresponding nutrients were provided

.

However, the nutrients they cannot synthesize are not the same

.

After growing the two mutants together for a period of time, some of the offspring of E.

coli actually regained the ability to synthesize these nutrients

.

After a series of experiments that ruled out other possibilities, the researchers concluded that E.

coli can pass genetic material to other bacteria, a process Lederberg calls "conjugation

.

"

The discovery quickly shocked the genetics community and earned Lederberg a share of the 1958 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

.

Now, we know more details about this process: A special type of pili, like a tube, exists on the surface of the bacteria

.

Using this fimbriae, it attaches itself to another bacterium and shoots out a "packaged" piece of DNA -- a plasmid

.

In this way, different bacteria, and even bacteria of different species, can "share" genetic material

.

Even the ability to grow fimbriae is transmitted this way

.

E.

coli grows fimbriae by relying on the F plasmid (F plasmid) in the body.

E.

coli that can grow fimbriae will mate with bacteria that do not have this ability, and allow one of the strands of the double-stranded F plasmid to be transferred through the fimbriae channel.

into another bacterium to synthesize complementary strands

.

In this way, the bacteria of the recipient can also grow fimbriae, and turn around and become a new supplier

.

Through the conjugation process of fimbriae, other bacteria can also acquire the ability to grow fimbriae (Credit: Adenosine - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.

0) But it is worrying that the transfer through the fimbriae channel, in addition to and bacteria In addition to the genes involved in hair formation, there are a large number of antibiotic resistance genes

.

Scientists quickly realized that in this way, bacteria could "take over" the resistance genes of other bacteria as their own, helping themselves to escape the attack of antibiotics

.

This is also the main reason why drug resistance is widespread and persistent in bacteria

.

Looting the "corpses" of companions For bacteria, conjugation is not even the only way to obtain DNA: In addition to obtaining DNA from living partners, they can also "loot" the "corpses" of other bacteria from outside the body

.

When bacteria die, they split open and release the DNA in the body, which becomes a "treasure" for other bacteria

.

In 2018, researchers at Indiana University recorded the scene where Vibrio cholerae stretches out its pili, hooks on a piece of DNA and brings it back into the body

.

The green fimbriae are like tentacles that "grab" the red DNA and drag it back into the body

.

(Credit: Ankur Dalia/Indiana University) Pili are extremely thin structures, only one ten-thousandth the size of a human hair

.

To see these fine structures, the researchers developed a unique dye that helps the bacteria "dye the fimbriae green"

.

Under the microscope, the green pili resembles a tentacle that "grabs" the red DNA and drags it back into the body

.

"It's like threading a needle

.

"The first author of the study, Courtney Ellison, said it was estimated that the diameter of the hole that the DNA passed through might be only 7-8nm in diameter, while the DNA that was caught was about 50nm long," If it weren't for these fimbriae, the chances of DNA entering the bacteria naturally through this small hole are very small

.

"Bacteria that look quiet under a normal microscope are actually stretching their fimbriae

.

(Credit: Ankur Dalia/Indiana University) Gut Bacteria Aid Digestion When it comes to this, you might think that bacteria are tricky

.

But in fact, these shared Behavior is also about better survival, and this is not necessarily all bad news for humans

.

In the latest study published in Cell Reports, the researchers focused on the phylum Bacteroidetes ( Bacteroidetes)

.

Bacteroidetes are important members of the human gut flora, and in some people, even account for 80% of the entire microbiome

.

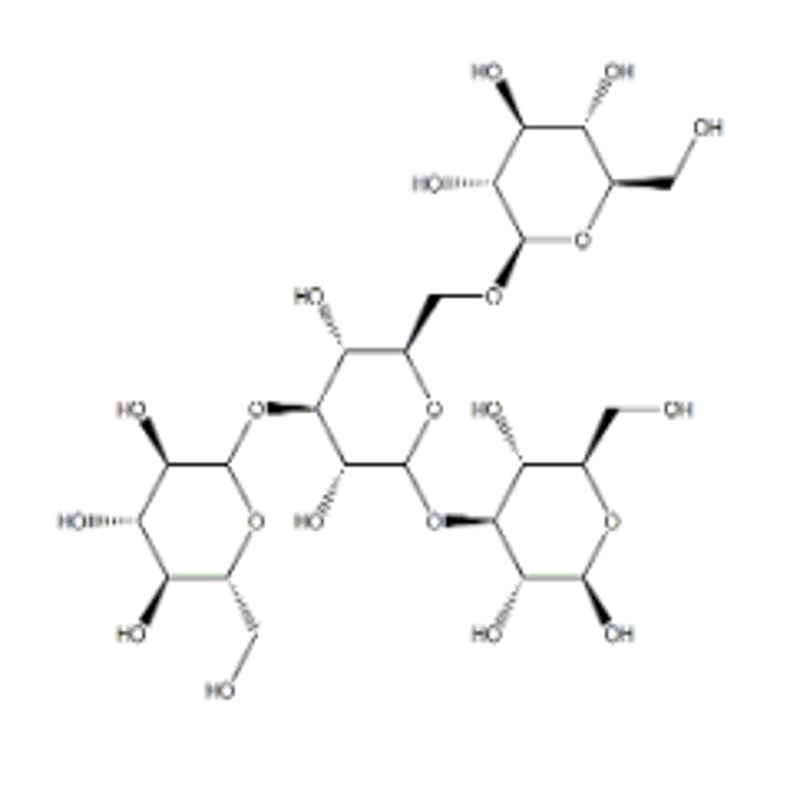

These Bacteroidetes are the main metabolizers of dietary polysaccharides.

"If you don't have them, you The large, long molecules in foods such as sweet potatoes, beans, and vegetables cannot be digested

.

They break down these foods so we can get energy from them

.

" Bacteroides bacteria can make up 30% of the normal human microbiome (Credit: NOAA/OpenStax Microbiology

)

It's not easy to settle in the gut and (by the way) help us digest carbohydrates

.

To do so, these bacteria must compete with other microbes in the gut for limited resources, including vitamin B12 and related compounds

.

Yes, your gut bacteria, just like you, need vitamin B12, which plays a key role in both bacterial metabolism and protein synthesis

.

The problem is that most microbes in the gut -- including most Bacteroides -- do not have the ability to synthesize B12 and related compounds on their own, which means they need to have efficient transport systems in place to absorb B12 from the environment

.

That's where sharing between bacteria comes in: the researchers found that bacteria in the phylum Bacteroidetes also share genes related to the B12 transporter by conjugation

.

B12 Transporter Before the formal study, Degenan and colleagues identified an important transporter responsible for helping gut microbes absorb B12

.

Then, Degenan began to wonder, how did these microbes acquire the B12 transporter? Could this process also be involved in bacterial conjugation? To prove this conjecture, Degenan and his team cultured bacteria that could absorb B12 alongside those that couldn't, as Lederberg's experiment did more than 70 years ago

.

After a period of time, those bacteria that were unable to absorb B12 survived and acquired the ability to absorb B12

.

To figure out where the gene came from, the researchers examined the entire genome of the bacteria

.

"For a given organism, their DNA bands are like fingerprints

.

Apparently, the recipient of the DNA has integrated an extra piece of DNA from the donor, showing that they received the new DNA from the donor

.

" De Gennan said

.

Experiments in mice yielded similar results.

When the researchers transplanted two species of Bacteroides (one able to transport B12, the other not) into the mouse gut, only 5-9 days later, the former The gene "jumps" into the latter body

.

"It's the equivalent of two (different hair color) people having sex, and now they both have red hair

,

" Degenan said

.

Another interesting new finding is that the paper points out that gene transfer between the same species is slightly faster than between two different species, suggesting that even bacterial sex may be subject to mild "reproductive isolation"

.

However, compared to most eukaryotes, this kind of sexual behavior is still much "wild"

.

Reference link: https:// https://news.

ucr.

edu/articles/2022 /02/01/human-gut-bacteria-have-sex-share-vitamin-b12https:// -bacterial-sex/https:// Related papers: https://profiles.

nlm.

nih.

gov/spotlight/bb/feature/bacgen1 / the picture or read the original article in the sale of the new issue of Global Science in February Buy now Click [Watching] to receive our content updates in time